My friend, John Broesamle, is a distinguished political historian and previous contributor to RINOcracy.com. My recent reference to the terms progressive and liberal sparked a gracious offer to provide some historical background, which I quickly accepted. Perhaps in another blog he will take us on a tour from “Socialist” to “Democratic Socialist.”

From “Progressive” to Liberal” and Back Again

John Broesamle

RINOcracy recently raised an excellent question: “Does anyone know just where to draw the line between ‘liberal’ and ‘progressive,’ or how the latter term came into its current usage?” I’d like to take a stab at responding. The answers aren’t simple.

The term “progressive” began to be used in American politics around the turn of the twentieth century to identify people who were agitated about the state of American society and politics at the time. Progressives believed the country had become a plutocracy with troubling concentrations of wealth and power at the top, a struggling middle class, and widespread misery at the bottom. Flagrant misbehavior by some of the biggest corporations inspired outrage. And progressives were appalled at the corruption that characterized government at all levels. They yearned for progress toward what one of them, Herbert Croly, called “the promise of American life.”

Progressivism originated at the local and state levels but went national when Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901. By then a Progressive Movement had emerged across the country and in every state. Though public opinion polling did not exist at the time, it is safe to assume that most Americans identified as progressive to one degree or another.

Theodore Roosevelt epitomized the progressive revulsion against corporate misbehavior, slum misery, and political corruption. Like progressives of every stripe, he reached the conclusion that addressing these problems required cleaning up government, separating it insofar as possible from corporate domination, and adopting regulatory legislation that would save capitalism from itself. Denied the Republican presidential nomination in 1912, he ran that year on the Progressive Party (“Bull Moose”) ticket. The party’s platform was easily the most important of the twentieth century. Among other things, it issued a call for some form of national health insurance.

Everything about progressivism circa 1912 has a familiar ring in 2019. What seems astonishing today, though, is the degree to which that earlier era of progressivism was bipartisan. While just as now the GOP was disproportionately conservative and the Democratic Party the reverse, progressives abounded in both parties. Indeed, until his untimely death in 1919, Theodore Roosevelt was the odds-on favorite to take back the Republican presidential nomination the following year. By 1920, though, progressivism as a movement had all but died.

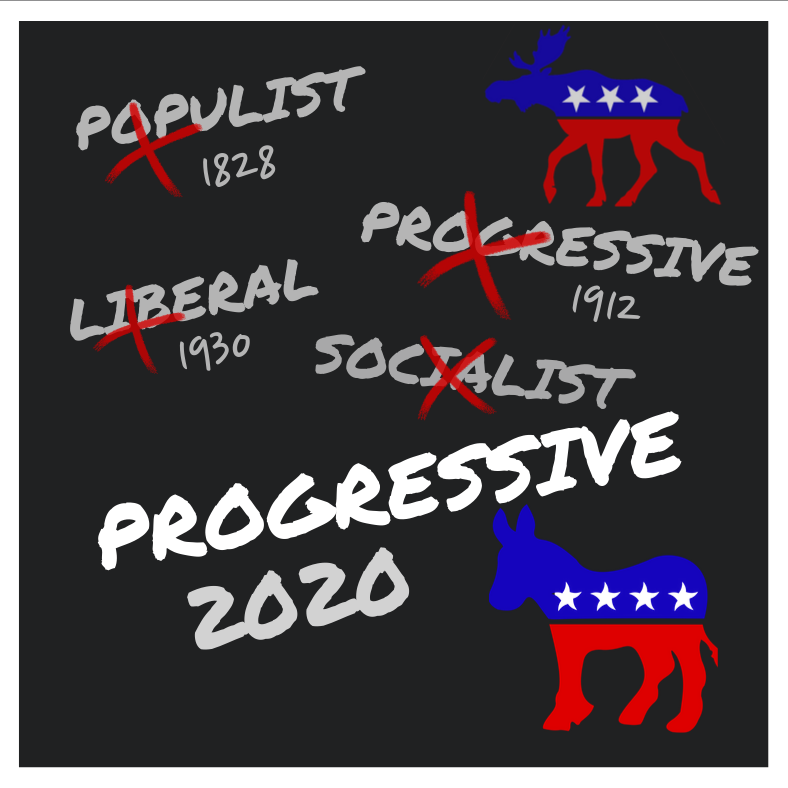

By the 1930s, the term “progressive” had given way to “liberal” in denoting a brand of reform seeking broad social and political change through the use and expansion of government. There were probably two main reasons for this switch of words—lingering disappointment that progressivism had not ushered in even more change than it did, and the sense among many old progressives that the New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt was going too far. New times required a new term. But liberal? The irony of calling the New Deal liberal lay in the emphasis that the classical liberalism of prior centuries had placed on economic freedom. The New Deal instituted the greatest antitrust campaign in American history, ushered in Social Security and the minimum wage, and did a lot of other things that caused free marketeers—neo-liberals in today’s vernacular—to revile FDR to this very day. Even so, throughout the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, a good number of Republicans subscribed more or less to the norms of New Deal liberalism. Dismissed as “me too” or “Rockefeller” Republicans, they included Nelson Rockefeller himself, Earl Warren, Jacob Javits, and John Paul Stevens.

Confusing? It gets more so.

By the 1970s, the term “liberal” was becoming a problem. Running for President in 1976, Democratic Representative Morris Udall of Arizona, who considered himself a liberal, began describing himself instead as a progressive. The word “liberal,” he remarked, had become associated not so much with the bread-and-butter reforms of the New Deal as with “abortion, drugs, busing and big-spending, wasteful government.” The liberal agenda had broadened over the past forty years to embrace civil rights, gender issues, and environmentalism, creating a whole new array of political targets. In turn, the Republican Party had done a superb job of identifying the word “liberal” with unpopular causes, wedge issues, and a standing accusation that liberals believed that anything goes. By 1976, the term was toxic, a “worry word,” as Udall put it. Rediscovered in the 1970s, by the 1980s “progressive” had become the accepted term for describing those on the center-left.

Recent years, though, have seen another turn of the wheel. By the Obama era, the meaning of “progressive” had blurred into what Nate Silver labeled “rational” as against “radical” progressivism. Rationalists were gradualists, building mostly incrementally upon established institutions and precedents. For radicals, progressivism blurred into various versions of socialism. Think Joe Biden vs. Bernie Sanders.

With the Democratic Party as a whole now being accused of socialism by the current occupant of the White House, the time has arrived to clarify what it means to be a progressive. It seems entirely fitting to stick with the term, since so many of our current national issues are exactly the same as during the original Progressive Era. Redefinition cannot happen, though, until the Democratic Party decides on who it wants for President and what its platform says.

About the writer. John Broesamle is Emeritus Professor of History at California State University, Northridge. His books on American politics and society include Reform and Reaction in Twentieth Century American Politics, Twelve Great Clashes that Shaped Modern America: From Geronimo to George W. Bush (with Anthony Arthur), and, most recently, How American Presidents Succeed and Why They Fail: From Richard Nixon to Barack Obama.

I second Randy Roth’s point: How might progressivism respond over the coming years? Also, I’d love to read some discussion of the devolution of ‘traditional’ Conservatism into the political cesspool it now is under Trump and McConnell.

Excellent historical perspective. Are we entering a new era of misery for the working class? Should Jacob Riess and Upton Sinclair be required reading for high school students? Is the middle-class bearing the brunt of Trump’s huge tax cuts on the top one-percenters and corporations?

It appears increasingly possible that Elizabeth Warren will be the Dems’ presidential nominee and (her left-wing populist message is catching fire) that she can beat Trump – our tyrannical and stupid president. But she will need broad support in Congress to achieve widely popular goals such as, a big reduction in healthcare costs; closer regulation of the financial industry; real tax reform; a balanced budget; a firm but fair immigration law system; renewed protection of the environment and our precious natural resources; and, perhaps most importantly, restoration of public trust in government.

Walter Lippman wrote that every thinking person is or has been a liberal, moderate and conservative. He was right to eschew political labels.

Thanks again, Professor Broesamie, for your thought-provoking post on Doug Parker’s blog. We can learn a

lot by studying history.

Fascinating discussion of the liberal versus progressive distinction, its changing use over the last 100+ years of our political history, and great to be reminded that it was Republicans underTeddy Roosevelt that were the first true progressives. How times have changed! Nate Silver’s differentiation of rational progressives and radical progressives is especially timely and relevant now, and with Trump and the GOP establishment in no way being true conservatives now, traditional conservatives have virtually no place to go. Moderate voters, whether Democrats or Republican, are in an equally uncomfortable place, caught in a very divisive political scenario of parties representing more extreme and combative views. Hardly a healthy situation for society, and our immediate political future!

Doug: thanks for inviting Professor Broesamle to shed some light on terms that have become murky. The root causes underlying progressivism, income inequality, corruption, etc. have their dopplegangers today. I’d be interested in Professor B’s predictions about how today’s progressivism will respond.

Comments are closed.