Since the coronavirus descended, Donald Trump has committed a series of political blunders that have undone prior presidents. Because he seems to defy the laws of political gravity, this might not make much difference in November. Right now, though, polling suggests that it already is. Considering presidential history, it certainly should.

The first classic mistake is an underlying condition—plain incompetence. Warren Harding (1921-1923) knew that he was out of his depth in the White House. “My God,” he once exclaimed, “this is a hell of a job!” The realization raised Harding’s level of insecurity and anxiety the way that Trump’s outbreaks of ranting, shouting, and tweeting reveal his. To Harding’s credit, he was perfectly honest about his predicament: “I am not fit for this office and never should have been here.” He presided over one of the most corrupt administrations in American history because he could not say no to what he called “my God-damned friends.” His dilemma resolved itself with a fatal heart attack.

Gnawing anxiety did not afflict Herbert Hoover (1929-1933). He emerged from World War I with a reputation as the world’s outstanding humanitarian, for having administered the wartime American food and economic relief program in Europe. He seemed exactly the man to confront the Great Depression when it struck in 1929. Or was he? Hoover did more than any prior president to combat a depression. It was not enough. Leery of giving federal aid to needy Americans (as opposed to needy Europeans), he feared it would undermine their character. In his final days in office, he declared: “We have done all we can do; there is nothing more to be done.” The precedent for today’s multi-billion and multi-trillion-dollar relief packages was set by Hoover’s successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Having initially embraced FDR’s spending strategy, Trump is now undecided about more such outlays to needy Americans, at a time when even conservative economists declare that more outlays are vital. Trump runs the risk of Hoover’s fate. Like Trump with Covid-19, Hoover continually insisted that conditions were getting better—that prosperity was just around the corner despite 25 percent unemployment, homelessness, and starvation. Hoover spent the 1930s casting blame on his successor in much the way Trump blames his predecessor.

A classic example of donning a straitjacket like Hoover’s is the tragedy of Lyndon Johnson (1964-1969). American leaders stepped into the Vietnam quagmire with considerable anxiety that the war was unwinnable. But Johnson believed he had no choice: “If I don’t go in now and they show later that I should have, then they’ll be all over me in Congress. They won’t be talking about my civil rights bill, or education or [highway] beautification. No sir, … Vietnam, Vietnam, Vietnam.” He became utterly single-minded about Vietnam, in the way that Trump has taken a damn-the-torpedoes position on reopening the country, “vaccine or no vaccine.” The consequences forced Johnson out of the 1968 presidential race.

The case of Johnson, like that of Harding, cautions strongly against electing to the presidency a deeply insecure person who feels besieged by friends, enemies, or both; but neither makes the case as strongly as Richard Nixon (1969-1974). White House Counsel John Dean characterized Nixon’s notorious, secret “enemies list” as a means of “dealing with persons known to be active in their opposition to our Administration; stated a bit more bluntly—how we can use the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies.” The remarkable thing about Watergate is that, from Nixon’s political standpoint, the break-in proved utterly unnecessary: in 1972 he won 49 states with 520 electoral votes. Donald Trump, who distrusts humankind in general, makes no secret of whom he regards as his enemies. He fires inspectors general; he threatens states that want to vote by mail; his remarks about Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi could blister skin. Is he capable of comprehending Nixon’s words in his farewell speech to the White House staff? “Always remember, others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself.”

Jimmy Carter (1977-1981) provides another case study that Trump might heed, had he a mind to—projecting helplessness. By his own admission, Carter became almost obsessive about the Iran Hostage crisis. Four hundred-forty-four days of constant press coverage highlighted Carter’s impotence, evoking, in Richard Nixon’s phrase, an image of America as a “pitiful, helpless giant.” In recent weeks there has emerged an op-ed literature at home and abroad inviting pity for a United States that, with no one at the helm, cannot find a course to steer. For Carter, the press drumbeat was a nightmare. Trump, though, feeds on corona publicity, staging press conferences featuring misinformation, wishful thinking, and eccentric medical advice. This may reassure his base, but it also spotlights his powerlessness over a mysterious, rampaging disease. Corona may wane; it may not; and what if, in the fall, it roars back?

Trump owns the corona crisis, like any other property, and he makes himself look weak.

In turning coronavirus policy over to the states, and leadership in the crisis over to governors such as Andrew Cuomo and Gavin Newsom, Trump has reverted to the precedent of yet another predecessor, James Buchanan (1857-1861). As the Civil War came on and the United States began to unravel, Buchanan froze. He considered slavery evil but denied that Washington had any authority to interfere with it. He thought the states had no right to secede from the Union but drew the line at stopping them. Seven slave states had walked out before Abraham Lincoln replaced Buchanan. Trump raises anew the federal-state conundrum, a question we had considered settled. For 160 years, Buchanan held the record for dithering in a crisis. Now he has a challenger.

Each of these past presidencies poses a warning to Trump, whose frequent allusions to history—“I believe I am treated worse” than Lincoln—demonstrate that he does not know any history. In conversation after conversation with other historians, I have heard them declare that they would bring back any prior president to replace the current one. I certainly would. No past president has remotely threatened the foundations of American democracy the way Trump has. The corruption around the White House today makes Harding’s cronies look like dime store shoplifters. No president has lied with the wild abandon Trump displays. And while a few earlier presidents have struggled with mental decline or depression, none prior to Trump has been unhinged. Compared to Trump, a James Buchanan or a Warren Harding seems strikingly balanced. As Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter Alice once remarked, “Harding was not a bad man. He was just a slob.”

About the writer. John Broesamle is Emeritus Professor of History at California State University, Northridge. His books on American politics and society include Reform and Reaction in Twentieth Century American Politics, Twelve Great Clashes that Shaped Modern America: From Geronimo to George W. Bush (with Anthony Arthur), and, most recently, How American Presidents Succeed and Why They Fail: From Richard Nixon to Barack Obama.

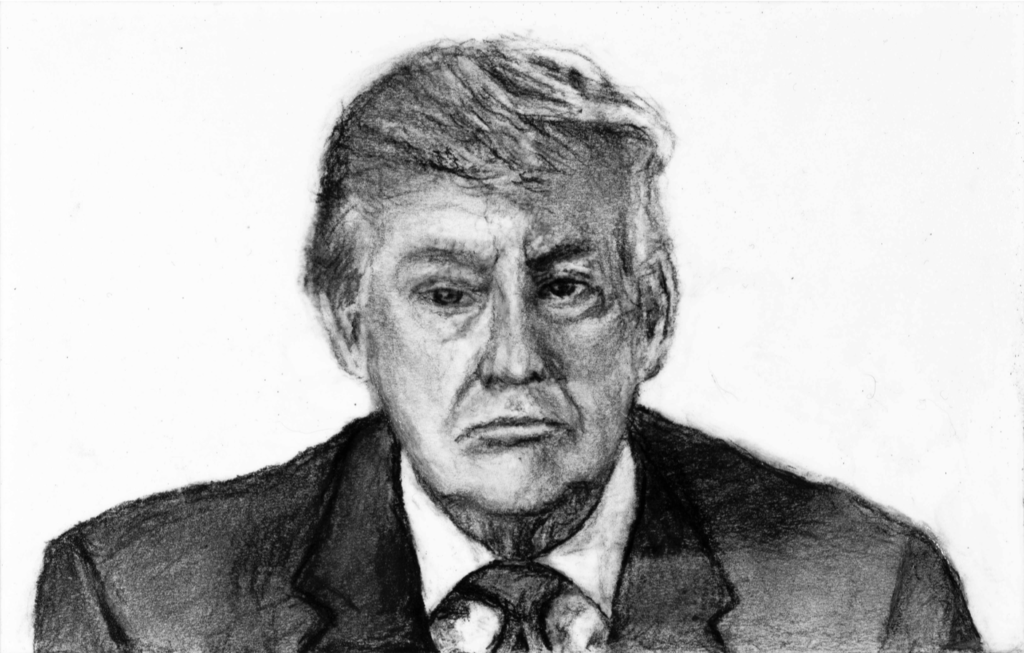

About the artist. The portrait of Donald Trump is by Sandy Treadwell whose work may be viewed at sandytreadwell.com. In an earlier life Sandy was New York Secretary of State from 1995-2001 and Chairman of the New York Republican State Committee from 2001-2004. From 2004-2008, he was a member of the Republican National Committee from New York.